- Home

- Celia C. Pérez

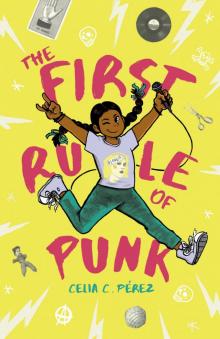

The First Rule of Punk

The First Rule of Punk Read online

VIKING

An Imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Penguin.com/YoungReaders

First published in the United States of America by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2017

Copyright © 2017 by Celia C. Perez

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Ebook ISBN: 9780425290415

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Pérez, Celia C., 1972– author.

Title: The first rule of punk / by Celia C. Pérez.

Description: New York : Viking, [2017] | Summary: Twelve-year-old María Luisa O’Neill-Morales (who really prefers to be called Malú) reluctantly moves with her Mexican-American mother to Chicago and starts seventh grade with a bang—violating the dress code with her punk rock aesthetic and spurning the middle school’s most popular girl in favor of starting a band with a group of like-minded weirdos.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017010474 | ISBN 9780425290408 (hardback)

Subjects: | CYAC: Individuality—Fiction. | Friendship—Fiction. | Mexican Americans—Fiction. | Punk rock music—Fiction. | Bands (Music)—Fiction.

| Middle schools—Fiction. | Schools—Fiction. | Chicago (Ill.)—Fiction.

| BISAC: JUVENILE FICTION/ People & Places/ United States/ Hispanic &

Latino. | JUVENILE FICTION/ Performing Arts/ Music. | JUVENILE FICTION/ Social Issues / Friendship. Classification: LCC PZ7.1.P44747 Fi 2017 | DDC [Fic]—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010474

Version_1

For Emiliano, for my mom, Gloria,

AND

In memory of my sister, Gloria A. Tuñon

1970–2012

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Acknowledgments,or People Who Led to This Book

Chapter 1

Dad says punk rock only comes in one volume: loud. So when I slipped my headphones over my ears, I turned the music up until bass strings thumped, cymbals hissed, and guitar strings squealed like they were having a conversation with each other. Mom says my music is a racket, but to me it’s like the theme music to my life. And it’s always helped me concentrate.

I ripped a page out of a magazine, then squeezed my fingers inside the blue plastic holes of an old pair of school scissors. It was a little too close for comfort, but my real scissors, the ones made of steel with a black handle, were packed away, and I had to get this done. It was now or never.

I maneuvered the blades carefully around the page. I liked the feeling of the scissors slicing through the glossy paper. Especially when I got to the very last snip and freed the exact piece I wanted. The word I cut out stuck to my sweaty fingertips, and I carefully placed it on the floor, where my zine supplies were spread out around me.

There were sheets of unlined paper and old magazines Dad had given me, an uncapped purple glue stick, and a folder so fat with clip art that papers spilled out of the opening. The yellow Whitman’s Sampler box that held my colored pencils, stickers, and scraps of paper still smelled of chocolate but no longer contained a delicious assortment of candy.

While hunched over the magazine, looking for more letters to cut out, a pair of leather-sandaled feet suddenly appeared. I looked up at Mom, who stood over me in her HECHO EN MEXICO T-shirt and a knee-length gauzy skirt. Her lips moved, but her words were no match for my music. Finally she pointed to her ears.

“SuperMexican strikes again,” I said, pulling the headphones down around my neck.

SuperMexican is my nickname for Mom. She’s always trying to school me on stuff about Mexico and Mexican American people. I think her main goal in life is to make me into her ideal Mexican American señorita. Plus, she likes to wear these embroidered dresses and skirts, and wraps called rebozos. I call this her SuperMexican uniform. Mom acts like it annoys her, but I think she secretly likes the nickname.

“Funny,” Mom said. “You all done packing?”

“I guess.” I glanced over at the pile of boxes and bags next to the door.

Mom told me to bring everything I needed but not to overpack, which didn’t make any sense. My room wasn’t my room without my things. There were only a few belongings I decided to leave behind, and they became the only signs that I’d ever lived here. I felt like someone had taken a giant Pink Pearl eraser and rubbed me out of the picture.

“Great,” Mom said. “Your dad will be here in an hour, so get ready.”

“I am ready.” I looked down at my T-shirt and shorts.

Mom’s eyes moved over my clothes with their super-scanning powers, looking for holes, stains, and other un-señorita-like offenses to point out. But before she could comment on anything, she noticed the magazine I was cutting.

“Malú, that’s not my new magazine that just came in the mail, is it?”

I gave Mom an unapologetic smirk to let her know that it was.

“I’ll take that, thank you very much,” she said, holding out her hand. “If you need magazines, check the recycling bin.”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said, and saluted before I handed her the copy of Bon Appétit.

I put my headphones back on and grabbed a blank sheet of paper. I had to get this zine done before Dad came to pick me up.

I started making zines earlier this year when I discovered Dad’s collection of punk music zines from his high school days. Zines are self-published booklets, like homemade magazines, and they can be about anything—not just punk. There are zines about all kinds of topics, like video games and candy and skateboarding. A zine can be a tribute to someone or something you love and nerd out about or a place to share ideas and opinions. Dad said they’re also a good way to write about what you’re thinking or feeling, kind of like a diary that you share with people. Mine are mostly about stuff I find interesting or want to know more about. But ever since Mom told me we were moving, a lot of my zines had become about that.

Mom made it seem like this move was no big deal because we’d be b

ack when her new job contract expired. But two years might as well be forever. Two years meant all of middle school. And I couldn’t even imagine what two years away from Dad would feel like. It was a very big deal. So for the next hour I wrote and cut and pasted a final plea to Mom. I glued the last letter onto a page just as the doorbell rang to signal that my time was up.

Chapter 2

When I walked into the living room, Mom was sitting on the couch, talking to Dad, her knitting bag next to her. The coiled scarf on her lap grew as her wooden needles clicked and clacked under and over and through the yarn. It was a hideous rainbow of pastels, like the tentacle of a Lucky Charms–colored sea monster. I scowled at the scarf and slipped the zine into Mom’s bag before throwing my arms around Dad.

“Lú!”

Dad scooped me up in a bear hug.

“Hmm, a gift for me?” Mom asked, glancing at the zine.

I nodded and straightened my T-shirt as Dad put me down.

“Malú, do you think you could wear something a little nicer?” Mom asked. “This is your last dinner with your dad for a while. It would be so lovely to see you looking like una señorita. I’d even settle for a fresh T-shirt.”

“She’s fine,” Dad said.

“See, Mom?” I grinned as obnoxiously as I could at her.

“Of course,” Mom said, looking from me to Dad. “Peas in a pod.”

She was right. Dad wore his usual ratty black Chuck Taylors, a black Spins & Needles Records T-shirt, and cutoff corduroys. I had on my Doc Marten boots, a black Ramones T-shirt, and cutoff khakis. Dad and I looked at each other and laughed.

“We’re twinsies,” I said.

“Really, it’s no big deal, Magaly,” Dad said. “We’re just getting takeout and hanging out at the store.”

“Come on, Dad.” I grabbed his arm and pulled.

“Fine, have a good night,” Mom said. “And don’t forget our flight is at noon, Michael.”

“I’ll be here with my chariot,” Dad said as he closed the door behind him.

We wheeled our bikes out of the yard, and Dad handed me my helmet.

“I hate that scarf,” I said through gritted teeth.

“Scarf?”

“Mom’s never-ending knitting project. It’s a bad omen.”

Dad laughed. “I didn’t know you were so superstitious,” he said.

“I’m serious, Dad. That scarf only appears when Mom’s stressed about something.” I snapped the chin-strap buckle of my bike helmet. “She was knitting all the time before she told me we were moving. Coincidence? I don’t think so.”

“Well, how about we forget the evil scarf for now?” Dad said. “We have some DaVinci’s to pick up. I ordered all your favorites.”

“Awesome,” I said. “Because right now it feels like I’ll never have DaVinci’s again.”

My mouth watered thinking about the food as we rode our bikes the few blocks to our once-a-week dinner spot. If I had to have a last meal on my final night at home, I wanted it to be DaVinci’s with Dad.

After we picked up our food, we rode back to Dad’s place, stopping under the sign that hung over the entrance to his store. The sign looked and spun like a real vinyl record. In the middle the SPINS & NEEDLES logo went around and around.

When Dad opened the door, Martí, his pit bull, ran out to greet us. Dad was funny about Martí’s name, always making sure people knew how to pronounce it properly.

“It’s Mar-TEE, like José Martí the Cuban poet, not MAR-tee like Marty McFly from Back to the Future.” Most times people would look at him like they had no idea what he was talking about.

After today I wouldn’t see Martí run through the door or hear Dad correct people’s pronunciation. Two more things to say good-bye to.

“What’s happening, buddy?” I asked, scratching Martí behind the ears. He wagged his tail and sniffed at me until he realized Dad had the food, then trotted off after him.

“Traitor,” I said, shaking my head.

“What do you want to listen to?” Dad asked from behind the counter.

“You pick it.”

“You know they’ve got some great record stores in Chicago,” Dad said. “You’ll have to check out Laurie’s Planet of Sound.”

“That’s great,” I said. “But it doesn’t matter because none of them will be this place.”

Spins & Needles wasn’t just a record store; it was my second home. Dad had owned it for as long as I could remember. He lived in the apartment upstairs. When I was sick and stayed home from school at his place, he would play quiet, soothing music because he knew the sound traveled upstairs easily.

I loved spending time with Dad at the store, listening to records. My favorite stuff was from the seventies and eighties, old punk that Dad always played. I helped him around the store too. I made sure the records were alphabetized in their correct bins, and I decorated the white plastic separators between bands.

But the best thing was being there when people crowded in to watch a band. The air would hang warm and heavy, and sometimes there wouldn’t even be room to pogo because the store would get so packed. The energy of the band and the crowd made me feel like there were hyper butterflies trapped inside me. The music would flow through the store like a magic carpet inviting me to hop on for a ride. You could stand so close to a band, it was like you were part of them. Some bands even welcomed people to sing along into the microphone. I always wanted to sing, but I never did because I was too scared.

“How’d you know I was in a Smiths mood, Dad?” I asked when the store’s sound system crackled to life.

The song started out with a jangly, quiet guitar and a voice that sounded sad but a little hopeful, too. Like when you’re stuck inside on a rainy Sunday and all you really want is for the sun to peek out so that you might be able to go outside, even for just a little while, before the school week begins.

“Just a lucky guess. Shall we dance?”

Dad grabbed one of my hands in his and put his other arm around my waist. I couldn’t stop giggling as he waltzed me around the record store and sang along. The song was about someone with crummy luck. I knew the feeling, so I joined in at the chorus, begging to get what I wanted for once.

Dad twirled me toward the counter and let go of my hand.

“Thanks for the dance, kid,” he said. “Now let me get some plates so we can eat.”

I gave Dad a thumbs-up and turned to the record bin labeled NEW (USED) ARRIVALS. I pulled out a record by a band I recognized and studied the singer’s face on the cover. The singer seemed to stare back, her hair teased and standing on end. She had her signature dark, heavily made-up eyes and lips. It was a look that made her a little scary, like an angry witch, but also kind of pretty. This reminded me of Mom and how she called punk music “a racket.” It always bummed me out that she could hear the anger but not the beauty in it like I did.

“I bet I could do that to my hair no problem,” I said. “What do you think, Dad?”

I held up the album cover for him to see.

“Sure,” Dad said, digging through a drawer for utensils.

“So you think it would be okay for me to do it?” I asked hopefully.

“You definitely have to ask your mom about that.”

“That’s not fair,” I said. “She’s making me move across the country. Can I at least decide how I look?”

“You’re entitled to feel that way, Lú,” Dad said, handing me a paper plate and a napkin. “But you still have to talk to your mom.”

“Sometimes I wish you two argued like normal divorced parents,” I mumbled.

“No, you don’t,” Dad said.

“Yeah, you’re right.”

I knew I was lucky. I liked that my parents got along even though they weren’t together. People always assumed my mom and dad were like other divorced parents,

who fought over everything, but they were actually friends. They split up when I was a baby, so I had no memories, just some old photos.

“Anyway, she doesn’t like how I dress, so what’s one more thing?”

“Mom doesn’t dislike the way you dress,” Dad said.

“Nice verbal gymnastics, Dad.”

“Really, she’s used to wacky outfits and loud music. She was married to me, wasn’t she?”

“No comment.” I grabbed a roll and stuffed the whole thing into my mouth.

“I think you and your mom are more alike than you realize.”

“SuperMexican and I are nothing alike,” I said through bread.

“You both do that scrunchy thing with your upper lip and nose.” He laughed just thinking about it.

“This is serious, Dad.”

“I know. I’m sorry.”

“I still don’t understand why I can’t stay with you.”

“I knew this was coming,” Dad said. The look on his face told me he didn’t want to have this conversation. “Malú, you know my schedule is too unpredictable. That’s why you live with your mom, remember?”

“But I’m almost thirteen,” I said. “And very responsible. You know that!”

“True,” Dad said. “But this is a done deal.”

I could feel my hope crumbling as if one of those huge wrecking balls used to tear down buildings had just slammed against it, turning it into dust. I thought of the zine I’d left for Mom.

“What if Mom changes her mind tonight?”

Dad gave me a look like he was questioning my grip on reality.

“She could,” I said indignantly. “Parents don’t always know best, you know.”

“Can’t argue with that,” Dad said.

I emptied my root beer can into a plastic cup and watched the foam threaten to spill over.

“Look, think of it as your big city adventure,” Dad said. “How many kids get to be in a new and exciting place for a while and then come back home?”

“Yeah, I must be the luckiest kid in the world.”

Dad opened the pizza box, and the warm smell of baked crust and melted cheese rose up, but my appetite had disappeared. Talking about moving had ruined my last DaVinci’s.

The First Rule of Punk

The First Rule of Punk