- Home

- Celia C. Pérez

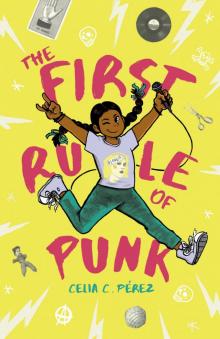

The First Rule of Punk Page 2

The First Rule of Punk Read online

Page 2

“Sorry, kid,” Dad said. “This is going to be hard for all of us, but we’ll get through it, right?”

Neither Mom nor Dad seemed especially torn up about it, to be honest. I could feel my eyes well up with tears, but I didn’t want to cry. So I grabbed a slice of pizza and busied myself by picking at the tomatoes and rearranging them into an angry face.

“Let’s not spend our last night together feeling sad,” Dad said. “Here, I got you a little gift.”

He pulled a small shoe box from behind the counter and placed it in front of me.

“A gift isn’t going to make me feel better,” I said. “But can I open it now?” I gave Dad a sheepish grin.

“Of course,” he said.

I pulled off the lid and picked up the small, oval-shaped yellow box that sat on top. It was so light, it felt empty. Inside were six tiny dolls that looked like stick figures, with ink dots for eyes and mouths. Each doll was about as big as my thumbnail, with cardboard limbs wrapped in colorful thread made to look like clothes.

“What are they?” I asked, carefully tapping the dolls out onto the counter.

“Worry dolls,” Dad said. “You put them under your pillow when you go to bed, tell them your worries, and they take them away while you sleep.”

“Do they really work?” I asked.

“You’ll have to tell me,” Dad said. “I thought they might come in handy.”

I nodded and scooped the dolls back into their tiny container. The other item in the shoe box was Dad’s old Walkman cassette player and a cassette in its plastic case.

“Cool! You made me a mix?”

“I put some new stuff and some old stuff on there,” Dad said. “I hope you like it.”

“Is the Walkman a gift too?” I asked, hopefully.

“How about I let you borrow it?” Dad said. “Return it when you’re back home again.”

I threw my arms around Dad and kissed his cheek.

“You may be far from home, kid, but you can take the music anywhere,” Dad said. “It’s always with you.”

“Thanks, Dad.”

“Hey, you want to play DJ?”

“Sure,” I said, and hopped off my stool.

Normally I loved playing DJ at the record store, but for once it wasn’t getting me out of my sad mood. Still, I pulled some of our favorites to play over the store’s speakers while we finished eating.

After dinner we cleaned up and took photos in the old photo booth, one strip for each of us. I looked around the store one last time, pretending my eyes were a camera, and snapped mental shots to tuck away for safekeeping. Then I turned off the lights.

Upstairs, Dad put on The Wizard of Oz while I changed into my pajamas. It was one of my favorite movies, and watching it together once a year had become our thing. I squeezed in between Dad and Martí on the couch. I always loved the beginning, where Dorothy’s in Kansas and everything is a brownish gray.

“Don’t listen to this part,” I said to Martí, covering his ears when Miss Gulch threatened to harm Toto.

I knew I was too old, but I snuggled close to Dad anyway and breathed deep into his shirt, trying to memorize his familiar smell of laundry detergent, peppermint gum, and sweat. I wondered when we’d be able to watch the movie together again.

“Dad?” I said, hesitating. I felt like a water balloon about to burst.

“Lú?”

“I know it’s not punk to be scared . . . but I’m scared.”

“It’s okay to be scared, Lú.” Dad squeezed my hand. “Hey, do you remember what the first rule of punk is?”

“There are no rules?” I asked.

“Okay, never mind,” he said, and laughed. “The second rule of punk?”

“The louder, the better?”

“You’re a real comedian.”

“I know, I know,” I said. “Be myself.” I’d heard Dad say the same thing five thousand times. “But how’s that supposed to help me?”

“Well, it’ll help you make new friends, find your people.”

“I have friends,” I said, before I could stop myself. “I don’t want new friends.”

Dad didn’t respond, but I knew what he was thinking. It was the same thing I was thinking. I didn’t really have any close friends at school. I considered Dad my people more than anyone else. I guess Mom was my people too, though she was different from Dad and me. It looked like I had a lot of people finding to do.

“I know,” Dad said, and nudged his chin toward the screen. “But you’re going to need a Yellow-Brick-Road posse.” He squeezed me tight and kissed the top of my head.

Dad kept telling me not to worry. That everything was going to be okay. I really wanted to believe him. But as I watched Dorothy’s house fly up into the air and spin around in the twister, I wasn’t so sure.

Chapter 3

“Welcome home,” Mom said, unlocking the door and dropping our bags at her feet.

“This isn’t home,” I mumbled under my breath.

The mat that was spread out in front of the doorway insisted otherwise. It read: HOME SWEET HOME. I did my best to avoid stepping on it and followed Mom down a long hallway.

“Well, it’s home for now,” she said, poking her head into each of the doorways. “It’s a little plain, but we’ll make it homey, right?”

“Sure, Martha Stewart,” I said. “But you know what else is homey? Our real home.”

“Malú, why don’t you go pick out your room?” Mom said, ignoring my snarky comment.

I leaned my suitcase against a kitchen wall and sat down on it, arms crossed.

“Come on,” Mom said. “You’re acting like a baby.”

“Am not.”

“You don’t want first dibs on rooms? Suit yourself.”

“Fine. I’ll go,” I said, getting up.

“I’m going to do some unpacking,” she said. “We can take a walk in a little while, check out the neighborhood.”

I grabbed my bags and wandered back down the hallway. We were supposed to live on campus in family housing, where other faculty and students lived with their families, but there were no apartments available, so someone in the English department helped Mom find this place. It was furnished in that generic way homes in furniture catalogs are. Nothing too personal or too bright or too different that might make it stand out in any way. Definitely no turquoise-colored walls like back home. Who would ever want to live in a furniture catalog photo?

One bedroom was bigger, but the smaller one had more windows, so that’s where I dropped my stuff. The bare walls were painted a pale green that reminded me of the hospital room where I recovered after I had my appendix taken out.

Looking around my new bedroom, I felt a tightness in my chest, like I couldn’t breathe. I pictured my heart and ribs blown from glass, tiny air bubbles throughout, like in the documentary about Mexican glassblowers I’d watched with Mom that summer. It felt like something was pressing down on me and my glass insides were going to crack into a million pieces.

I couldn’t stand looking at the empty walls, so I opened my backpack and took out my folder of pictures and articles I had up on the walls of my room back home. Most images were of my favorite bands, stuff I’d torn out of magazines or printed from the Internet. I tacked up my favorite picture of Poly Styrene of the X-Ray Spex in her sausage-and-eggs dress, and Frida Kahlo on the cover of Mexican Vogue. The last thing I put up was the photo booth strip of me and Dad at Spins & Needles.

When I was done, I pulled out my zine supplies and a sheet of paper that I folded into eighths.

“Good choice,” Mom said, appearing in the doorway. “We can paint if you want. Maybe get some curtains?”

“Sure,” I said, tucking the papers inside a book.

“You hungry?”

“Not really,” I said. “I think there mig

ht be a bowling ball sitting in my stomach.”

“A bowling ball, huh?”

“And it’s not one of the small ones for little hands, either,” I said. “It’s the biggest size, like the ones Dad uses.”

“Sounds bad,” Mom said. “Why don’t you try to walk it off? You don’t have to eat, but I think you’ll feel better.”

“Can I just stay here and work on this?”

“You can’t hole up inside, Malú,” Mom said.

“I can’t?”

Mom walked over and hooked her arm through mine. I had no choice but to let her pull me back down the unfamiliar hallway.

“Come on,” she said. “You can finish working on that later.”

“Can I bring my skateboard?”

“If it will get you out of this funk,” Mom said with a sigh. “Just be careful.”

“I will.” She was always paranoid that I’d break a bone if I so much as looked at my skateboard. Or, maybe even worse, fall and show my underwear to the world.

In the hallway Mom fumbled with the key in the lock, when the door across the hall opened and a pair of dark shiny eyes peered out. A tiny old woman waved at us.

“Hola, muchachas, everything okay?” the woman asked.

She stepped out from behind her door wearing a white housedress with a unicorn print. Her hair was gathered into a stubby bunny tail at the nape of her neck. Little salt-and-pepper tendrils escaped and curled around her ears.

“Hola, señora,” Mom said with a smile. “No problem, just the lock acting a little funny.”

Mom finally managed to lock the door and pulled the key out with a frustrated yank.

“That lock is a pain in the nalgas,” the woman said knowingly. She walked over to Mom and grabbed her hands like she’d known her forever. I could tell Mom was a little startled.

“Soy Oralia Bernal,” she said. “Welcome to the building.”

“Gracias, Señora Oralia,” Mom said. “I’m Magaly Morales. This is my daughter, María Luisa.”

Mom insisted on introducing me to people by my full name, which was so annoying.

“Hi,” I said. Señora Oralia shuffled over to me, grabbed my hands in hers, and squeezed them. Her hands were brown, darker than mine, and covered in faint wrinkles that made them look like paper bags someone had balled up and then tried to smooth out. They reminded me of my abuela’s hands. Except Abuela never wore nail polish, and Señora Oralia’s nails were painted a glittery purple.

“Bueno, bienvenidos,” Señora Oralia said.

She looked between us and smiled. I caught the glint of a silver tooth. It reminded me of a character in a book I’d read, and for a moment I wondered if Señora Oralia was a witch too.

“This is a good building. Quiet,” Señora Oralia said. “If you need anything, just come by. I’m here all the time, except when I’m not.”

She let out a raspy chuckle.

“That’s so nice of you,” Mom said. “We’re going out to explore, but I’m sure we’ll see you again soon.”

“Sí, claro,” Señora Oralia said with a little wave. “Have a good time, muchachas.”

I forced a smile and watched as she slipped back into her apartment.

“She seems nice,” Mom said once Señora Oralia was gone.

“I guess.”

“So, there are a lot of great-looking places around here. I did a little research online. How about Ethiopian? They serve your meal on a round tray covered with a big piece of injera and everyone shares.”

“What’s injera?” I asked.

“It’s like a spongy sourdough bread,” Mom said. “You use it instead of utensils to eat your food. Neat, right?”

She grinned like it was the most exciting thing she’d ever heard. There was only one thing I really wanted to know.

“Is there cilantro in Ethiopian food?” I asked.

“Hmm, I’m not sure,” Mom said. “But we’ll check, okay?”

We headed down our street, me rolling slowly on my skateboard next to Mom.

“You nervous about school?”

“Nope,” I said, and gave her a big, fake smile. “It’s always been my dream to be the new kid in seventh grade.”

“I’m so glad you got my dry sense of humor,” Mom said. “It’s okay to be nervous, you know.”

“Punks don’t get nervous,” I said, even though I was nervous. Super nervous.

“That makes one of us,” she said. “Maybe I should try being a punk.”

I rolled my eyes, but Mom didn’t even notice. Her brow furrowed the way it does when she’s in a work trance, like she was already thinking about her great new job and had forgotten all about me.

“Your school is close if you want to do a walk-by,” Mom said. “Might be good to get the lay of the land.”

“I can wait.” I wanted to avoid going anywhere near that place until I absolutely had no choice.

“I think you’re going to like it here, Malú,” Mom said. “There’s so much art and culture and history; it’s right up your alley.”

“Have you noticed that even the sky looks different here?” I asked, changing the subject. “I think it’s less blue.”

I glanced up at the trees that lined our street.

“Please don’t take your eyes off the sidewalk when you’re riding that thing,” Mom warned.

“And there’s no Spanish moss,” I said. “No lovebugs, either.”

“I won’t miss having to wash those bugs off the car,” Mom said with a shudder. “To be honest, I won’t even miss having a car!”

“I’ll miss them,” I said, even though I’d never thought twice about the bugs when I was home.

“Malú, we’re in Chicago,” Mom said. “You’re acting like we’ve moved to another planet.”

“I feel like I’m on another planet,” I said, pushing my foot harder against the sidewalk to gather speed. “I’m just waiting for the flying monkeys to appear.”

Mom laughed as I passed by her on my skateboard.

Chapter 4

Mom spent the week dragging me around the city to explore. We rode on the “L,” the trains that travel all over Chicago. We went to Lake Michigan, which was freezing cold for September and not salty like the Atlantic. We saw SUE the T. rex at the Field Museum, and Seurat’s people in the park, painted from tiny dots, at the Art Institute. We visited the biggest public library building I’d ever seen, where I got a new library card and a stack of books. We had egg custard buns and tea at a bakery in Chinatown. And we almost got swept up into a White Sox game before Mom came to her senses and remembered she didn’t even like baseball.

Then one day, while searching for a bookstore Mom wanted to visit, I saw Laurie’s Planet of Sound. It looked even cooler than Dad had described it. I thought about asking Mom if we could check it out, but I didn’t. It felt too weird to think about being in someone else’s record store. Plus, I figured Mom wouldn’t be interested. But it didn’t matter because she spotted her bookstore before I could say anything.

By Sunday morning all I wished for, besides going back home, was to be left alone with my music, my zine supplies, and my denial that school was starting. SuperMexican, of course, was not having it.

“Let’s go get some breakfast,” Mom said. “I saw a cute little coffee shop on my way to the train the other day.”

“No, thanks. I’m just going to eat some cereal.”

“Come on,” she said, yanking my comforter. “It’s our last day before school starts. Let’s have a nice breakfast together just like old times, okay?”

I pulled the blanket back over myself.

“I’ll bring some work,” Mom offered. “You won’t even have to talk to me.”

“You promise?”

“Just kidding,” Mom said. “Let’s go.”

Grrr

r.

“And can you please put on a clean shirt? You’ve been wearing the same one for days now.”

I sniffed my T-shirt. “Smells fine to me.”

The coffee shop we walked to had a bright red awning that said CALACA COFFEE. The large glass window was decorated with colorful skulls, marigolds, and dancing skeletons. I had to admit, Mom was right. It did look kind of cool.

Inside we were greeted by a life-sized papier-mâché skeleton that looked like Frida Kahlo with her blackbird eyebrows. A skeleton monkey was perched in her bony arms. It was Frida’s pet monkey, Fulang-Chang. Frida was one of my favorite artists and not just because I was almost named after her. I like that she painted about herself and her life and that she was outspoken. She was pretty punk rock! Near Frida was a shelf crammed full of books. I liked this place already.

There were steps leading up to a loft area with floor seating where pillows of mismatched colors, patterns, and sizes surrounded a few short tables. A woman with a bright pink stripe running through her dark hair cleared off a table. The sleeves of her shirtdress were rolled up to her elbows, revealing colorful tattoos on both arms. I couldn’t stop staring.

“Can we sit up there, Mom?”

I set one foot on the first step leading to the loft. Mom looked like she was going to say no, but the tattooed woman noticed us before she could.

“You can sit anywhere,” the woman said. “I’ll bring you some menus in a minute, okay?”

Mom smiled in acknowledgment and headed up to the loft.

“I’m going to look around,” I said.

“Go for it.” Mom pulled her planner out of her bag.

I slid my skateboard under our table and wandered toward the ordering area.

The display case beneath the counter was filled with pan dulce, sweet Mexican breads, that I remembered eating when I visited my abuelos. Each tray had a little sign in Spanish and English indicating the names of the different types of bread: LA CONCHA/THE SHELL; EL BIGOTE/THE MUSTACHE; LA OREJA/THE EAR; EL MARRANITO/THE PIG. They were named after what they looked like. My favorite was always the concha because it had sections of sweet, colorful icing on top that I liked to peel off and eat separately.

The First Rule of Punk

The First Rule of Punk