- Home

- Celia C. Pérez

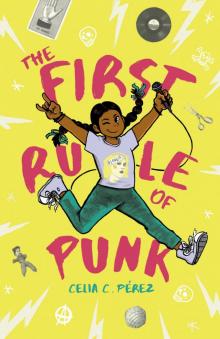

The First Rule of Punk Page 4

The First Rule of Punk Read online

Page 4

When I walked up to Ms. Hernandez’s desk, she was flipping through a thin, spiral-bound book. Printed on the cover was José Guadalupe Posada M. S. Student Code of Conduct.

“I could be wrong, Malú, but according to this, I think your makeup is a dress-code violation,” she said, putting the manual down. “You’ll need to go to the auditorium.”

“Am I in trouble?” I asked. Punks don’t worry about getting in trouble. But this punk still had to answer to her mom.

“No, of course not. It’s only the first day of school,” Ms. Hernandez said. “But Principal Rivera wants everyone to be clear on the dress code.” She held out a copy of the manual for me to take.

“Collect your things and head down there,” she said. “It’s at the end of hall.”

I nodded and walked back to my desk. I could feel Selena watching me as I stuffed my notebook and the code of conduct booklet into my backpack.

“Welcome to Posada, María Luisa,” she whispered before she and Diana broke into a fit of giggles.

Chapter 7

“Everyone, please sit toward the front,” a man called from the stage. He was short and skinny with glasses and a beard that matched the little bit of hair on either side of his head. He waved his hands wildly, urging us forward.

I looked around at the other kids who’d been sent by their homeroom teachers and tried to figure out why. One kid had on a T-shirt with a cartoon character mooning everyone. Another kid had pants belted just above his knees. Some kids were harder to guess, but we were a herd of dress-code violators, and the man on the stage was corralling us.

A boy with blue hair sat down in the seat in front of me. His hair looked punk, but nothing else about him did. He reminded me of someone out of a Beverly Cleary book, with his plaid short-sleeve button-down shirt, cuffed jeans, and black Converse high-tops. Like a brown-skinned, blue-haired Henry Huggins.

The man came down from the stage and handed out copies of the student code of conduct.

“I’m Mr. Jackson, a guidance counselor here at Posada,” he said. “And you are the lucky few who got picked for a personal introduction to the school’s dress code. I need everyone to take a few minutes to read over the list on page two.”

I opened the copy Ms. Hernandez had given me and read. No leggings as pants. No pajama bottoms. No clothes with inappropriate graphics or language. No spaghetti straps or crop tops. No flip-flops or slippers. No physical alterations that are deemed potentially disruptive, including, but not limited to, unnatural hair color, makeup, or piercings. No pants hanging below the waist. Skirts and shorts must pass the “fingertip test.” The list seemed to go on.

Mr. Jackson passed out another sheet of paper.

“This is a letter to your parent or guardian,” he said. “Please fill in your dress-code violation. These need to be signed and returned to your homeroom teachers tomorrow.”

“This is ridiculous,” someone muttered.

“And unfair,” the boy with the blue hair added. “You know how long it took me to get my hair this color? All summer, Mr. Jackson. Mexican hair ain’t easy to dye.”

Everyone laughed.

“How is my tank top the same as old raccoon eyes over here?” a girl asked, gesturing at me.

The blue-haired boy turned around and we made eye contact.

“Radical, dude,” he said in jokey surfer speech before turning back. “Mr. Jackson, my hair is me showing school spirit. I thought that would be appreciated.”

Mr. Jackson smiled. “I can see that,” he said. “But these are the rules, guys. Don’t like them? Figure out a constructive way to express yourselves.”

I imagined Mom’s I-told-you-so look as I filled in my dress-code violation: disruptive physical alteration. In parentheses, I wrote rad makeup.

Mr. Jackson spent the rest of our time in the auditorium trying to figure out ways each of us could fix our dress-code violations for the day. The kid with the cartoon character on his shirt was sent to the restroom to turn the shirt inside out. The girl with the tank top was given a POSADA PHYS. ED. DEPARTMENT T-shirt to put on. The boy with the blue hair was told to come back “with a normal hair color” the next day.

“What’s ‘normal,’ right?” the boy asked me as he stuffed the letter into the back pocket of his jeans and headed to class. One by one we were dismissed.

“Wow,” Mr. Jackson said, stopping in front of me. “What’s going on with this look?”

“It’s punk,” I said with a shrug.

“Well,” Mr. Jackson said. “You’re going to have to do punk some other way, young lady. Go ask the school nurse for a wash cloth, see how much of that you can scrub off.”

He handed me a hall pass and moved on to the next kid. I left in search of the nurse’s office, feeling not at all punk.

Chapter 8

At lunch I grabbed an orange plastic tray and stared at the chafing dishes full of food, unsure what to take.

“Yummy, right?” A tall, long-haired kid in front of me grinned as a lunch lady dropped a spoonful of something yellow that looked like creamed corn onto his tray.

I looked back at the food on the other side of the plastic divider.

“I can’t even decide. It all looks so good,” I said.

“I have a system,” he said. “I choose my food blobs by color. No neutrals. Only brights.”

“Does that work?”

“Not really,” he said. “It’s all terrible.” He picked up the instrument case he’d set on the floor and moved on down the line.

“Awesome,” I said. But I took his advice. I avoided the gross meaty brown blobs and settled on a green blob, an orange blob, and a red blob.

The cafeteria was noisy with kids laughing and talking sometimes in English, sometimes in Spanish, and sometimes in a combination bouncing back and forth between languages. It was strange to hear so much Spanish. Back home I almost never heard it unless Mom spoke it or happened to be listening to something in Spanish.

I found a place to sit alone near the entrance for an easy escape, should I need it. It’s a known fact that behind a book is always a good place for hiding and people-watching, so I pulled out my copy of The Outsiders, the book assigned to us in English class. From my hiding place I looked around for where I might fit in. Where were my people?

I watched the kid from the lunch line sit down at a table with other kids who had instrument cases. The blue-haired boy who had been in the auditorium that morning slipped into a seat at another table.

Nearby, Selena sat with Diana and a larger group. I watched them like I was an anthropologist. Being an anthropologist was my second career choice after musician in a punk band, so I studied Selena and her friends as if they were a newly discovered culture.

The boys wore baggy jeans, puffy basketball sneakers, and huge shirts. The girls all wore similar outfits of tight jeans and T-shirts with stuff like CUTIE and SRSLY printed on them. Like Selena, they all wore candy necklaces. There should be something about candy accessories and misspelled words on clothes in the dress code.

Selena looked in my direction, and I slid down in my seat a little, hoping she hadn’t spotted me. Unfortunately, she had. She got up and walked toward me, arriving in a cloud of vanilla-scented perfume. She stood there as if waiting for an invitation to sit, but I didn’t take my eyes off my book even though nothing was coming into focus. Selena wasn’t leaving.

“Hey, María Luisa,” she finally said, sitting down next to me.

“It’s Malú,” I said.

“So did you get in trouble this morning?”

“No,” I said. “Are you disappointed?”

She stuck her thumb under the elastic of her candy necklace, pulling on a pink candy circle. She brought it to her mouth and bit into it. The circle cracked, and a tiny piece of pink flew onto my tray.

“Look, I’m not here

to bother you,” she said, giving me a sly smile that said otherwise.

Dad said being punk was about being open-minded, and that included giving people the benefit of the doubt, but I wasn’t convinced Selena was trying to be nice.

“Where’d you move from?” she asked.

“Florida.”

“Florida, huh? You ever go to Disney?”

I shook my head.

“I’ve been twice,” she said. “With my dance school.”

This was probably when having friends came in handy. I was like a nation of one in the cafeteria with no one to help defend the territory.

“I know it’s probably hard being new, so I thought you could use some help,” Selena went on, finally getting to the point of her visit.

“What kind of help?” I asked, taking the bait.

“You know, someone to teach you how things are around here,” she said. “Trust me, it’s a good thing they made you wash off that makeup. Only a coconut would do that kind of thing.”

“What’s a coconut?” I asked.

“Of course you don’t know what that is,” Selena said. “Never mind.”

She looked at the hole in my jeans and made a face.

“The point is, try not to be a weirdo. If you can.”

She said the word weirdo like it was a terrible disease I didn’t want to catch. I started to feel my ears burn like they do when I’m angry.

“I just want to read my book, okay?” I said, hoping she’d lose interest and move on soon.

“You see those guys over there?” she asked, not taking the hint. “Why do you think they’re sitting alone?”

She pointed to where the blue-haired boy sat with another kid. They didn’t look alone to me.

“Weirdos,” she whispered. “You don’t want to end up at that table.”

I glanced at the table where her friends sat looking our way.

“I think I’d rather be at that table than yours,” I said.

“Is that how you treat someone who’s trying to be a friend?” Selena pretended to look hurt. “Listen, I know a weirdo when I see one,” she said. “And I’m trying to save you from yourself, María Luisa.”

“Can you just go back to your table and leave me alone?”

“Fine,” Selena said, getting up. “Let me know if you change your mind.” She looked down at my shoes. “Is that tape?”

I stared at the duct tape that peeked out over the sides of my shoes.

“Wow,” she said. “You really do need help.”

She made a disgusted face and walked off, leaving me feeling like something really low. Like a piece of tape stuck to the bottom of someone’s shoe.

Chapter 9

As soon as I opened the front door after school, I wished for a secret entrance that would let me go straight to my room without having to face Mom.

“I’m in the kitchen,” she called out. “Come, I want to hear all about your day.”

I dragged my feet to the kitchen, where Mom was almost finished painting one wall a bright tangerine color. She was wearing her work-around-the-house clothes: overalls and an old MEChA T-shirt.

“You like it? I’m not going to paint the entire place, but I thought it could use a little color.”

“It’s nice,” I said, thinking no amount of paint would make me like this place.

“Speaking of color,” she said. “What happened to your makeup?”

She asked it in a way that sounded like she’d already figured it out but wanted to hear me say it.

“Yeah, about that . . .” I said, digging into my backpack. “Here.”

Mom took the sheet; a frown appeared on her face as she read it.

“What did I tell you? First day and you have a strike against you.”

“It’s not a strike, Mom,” I said. “It’s a warning. Anyway, at least my underwear wasn’t showing like another kid who got called into the auditorium.”

“Pen,” Mom said, and held out her hand. “Let’s try for less punk rocker and more señorita from now on.”

“Can’t I be both?” I asked.

She gave me her I’m-not-joking look and handed me the signed paper.

“Don’t make me go through your clothes and throw out all those holey pants and shoes,” she threatened.

“Fine,” I said. “I’m going to call Dad. I promised I’d call as soon as I got home.”

“Wait, did you make any friends?” she asked. She looked so hopeful. Sometimes I wonder if Mom even knows me.

“Not really.”

“Not really, no? Or not really, yes, but you don’t want to tell me?”

“Not really, not really,” I said.

“How about José? Did you find out who he is?”

“I was too busy just trying to survive, Mom.”

“Okay, don’t tell me anything,” Mom said, turning back to her painting. But I knew she wouldn’t give up that easily.

I opened the refrigerator and grabbed a cheese stick.

“I was reading a little bit about your school’s namesake today,” Mom said. “Did you learn anything about José Guadalupe Posada yet?”

“Only that he was a pretty sharp dresser,” I said. “I’m also guessing he was a very serious man.”

“What in the world are you talking about?”

“There’s a portrait of him in the hallway near the office,” I said, and bit into my cheese stick.

“Cute,” Mom said. “You might actually be interested in him. He was known for his political cartoons.”

“Cartoons? Cool.”

“And his calaveras,” Mom went on.

“What’s a calavera?” I asked.

“They’re skulls, or skeletons,” she explained. “Like the ones that are up at Calaca. Which, by the way, means—”

“Wow, Mom, how did you know?” I asked.

“What? About Posada?”

“No,” I said. “That what I really needed after a long day at school was another history lesson.”

“You are such a smart aleck,” Mom said. “Anyway, he’s an important figure in Mexican history. It’s important to know about our history, Malú.”

“Your history,” I said. “I’m only half Mexican.”

The conversation made me think of Selena. Another thing I didn’t want to do after a long day at school.

“Our history,” Mom repeated.

“Okay, SuperMexican.”

I pictured Mom flying through the air with a rebozo cape billowing behind her and stifled a giggle.

“What’s so funny?”

“Nothing,” I said, but I had just gotten an idea for a zine.

“I’ll make some pasta for dinner as soon as I finish this,” Mom said. “Unless you want to help?”

“Sorry, gotta call Dad,” I said. “Plus tons of homework.”

“On the first day? Very strange.”

“You wouldn’t believe it,” I said, backing away.

“Tell your dad I said hello.”

I slipped out of the kitchen before Mom could stick a paintbrush in my hand.

In my room I threw myself on the bed and called Dad. The worry dolls were scattered everywhere, so I collected them and lined them up again neatly under my pillow. As I told Dad about being sent to the auditorium and about Selena making me feel like a freak, my insides clenched. It felt weird to say her name out loud to Dad. Like I was opening a door and letting Selena into my world, and I didn’t want that at all.

After I hung up, I grabbed Dad’s Walkman and hit play on his mix. As the bouncy, poppy-punk song filled my head, my insides relaxed and expanded. I couldn’t deal with the even-numbered problems that awaited me on pages nine and ten of my algebra book, so I pulled out my zine supplies instead.

Chapter 10

I made it my mission to avoid Selena as much as possible in the cafeteria, but it was like the fates conspired to bring us together in the worst possible place: Spanish class. There was one class for nonnative speakers, and all the rest of the periods were for fluent speakers. I was surprised to find out that I’d tested into the fluent class, since my Spanish sounded like it had been put in a blender and pulsed into a mess of sounds and letters. Selena’s Spanish was, of course, perfecto.

“En español, señorita,” Señor Ascencio reminded a girl named Beatriz who had asked to go to the bathroom. She let out a dramatic sigh.

“¿Puedo ir al baño, por favor?” she asked.

“Sí,” he said. “Vaya rápidamente.”

When class started, Señor Ascencio explained that we each would have to create a family tree and write a short essay to go with it for our first big assignment due on Monday.

“¿Para cuándo, Señorita O’Neill-Morales?” he asked me, trying to confirm the due date for the assignment.

I sat up in my seat to answer, but before I could say anything, Selena interrupted.

“Señor Ascencio, María Luisa no habla español.”

Some kids laughed, and I could feel my ears burn. Señor Ascencio ignored Selena and asked the question again.

“Para el lunes,” I said through what felt like a mouthful of marbles.

“¡Muy bien, Señorita O’Neill-Morales!” Señor Ascencio read each word out loud as he wrote para el lunes on the board. “Para cuando vengan sus padres.”

Great, the trees were going to be up at back-to-school night for everyone to see. Including Selena and her judgy little eyes.

I focused on finishing the workbook pages that were due by the end of class and placed them on Señor Ascencio’s desk. Back at my seat, I worked on a zine for the rest of the period. I was putting away my supplies when a hand snatched the zine from my desk.

“What’s this?”

Selena held it between two fingers like it had cooties.

“Give that back!” I said through gritted teeth. I lunged for it, but she took a few steps out of my reach.

The First Rule of Punk

The First Rule of Punk